Exploring the Heart of Modern Love with Philippa Found

Philippa Found has become a quiet archivist of how we love, lose and muddle through connection. After capturing the raw tenderness of the pandemic era with Lockdown Love Stories, Found returns with It’s Complicated: Collected Confessions of Messy Modern Love, a braver, messier and more expansive exploration of modern relationships in all their forms. In a dating landscape shaped by burnout, blurred boundaries and emotional shorthand, her new book shifts the focus beyond romance to the sustaining power of platonic love, emotional intelligence and honest communication.

From pining over exes for a decade to doubting fiancés, ghosting, friendships, fuckboys and the quiet comfort of platonic love, Found’s work cuts through the glossy romance of social media to reveal something far more familiar: confusion, tenderness and a lot of unfinished endings. In this interview, she reflects on what collecting these stories has taught her about emotional intelligence, dating myths, and celebrating our failures, because life, as she reminds us, isn’t a highlight reel, it’s a shared, chaotic, deeply human experience, and there’s solidarity to be found in every imperfect chapter.

MR: You first launched the anonymous love-stories project as an artwork. At what point did you realise it had become something much bigger and more necessary than that?

PF: Almost straight away, I always thought this could be something bigger. So I was like this crazy art girl going out during lockdown, chalking out the website URL across parks. I intended to create an online portrait of society, a kind of self-portrait of our collective experience on my site. I didn't know if anyone would actually share their stories; it was an experiment. And I remember after reading the first three stories, I was like, "Oh my god, I have never read anything like this.” I was immediately addicted to the stories.

MR: Yeah, I think I would be the same.

PF: I was totally hooked. I was like, "This is so cool." I've never heard someone admit that they were having sex dreams about Robert Patterson spitting on them. It was so raw and unfiltered. This is exactly what I was hoping for: that by making it anonymous and creating a completely anonymous space, people would feel comfortable sharing and being candid, knowing they couldn’t be traced.

MR: Yeah, there's freedom in anonymity.

PF: And I just thought I'm reading things I've never read about, and I'm not only finding their words fascinating, but I'm finding it really helpful. It made me feel less lonely knowing that I wasn’t the only one who had these kinds of conflicting feelings about relationships. And knowing that other people are also holding on or struggling made me feel less alone. I mean, it doesn't change the situation you're in, but it does remove the shame. And the biggest antidote to shame is knowing someone else feels the same way as you. So reading these stories and knowing I wasn't alone immediately alleviated the shame.

And I think the other thing that was a real driving force for me was knowing that this was bigger than me. I started posting on Instagram, and people would comment on the stories or DM me, and I realised it wasn't just me that these stories were helping people. It was like this collective experience, and I wanted to keep doing it basically. The beauty of the material is that it was so transferable across loads of media, and obviously, it's text, so a book makes sense, but I never thought I'd get enough stories to make a book. And then it just became like this real thing.

MR: Yeah, and it was also the right time as well. I feel like during lockdown, people were willing to share more, and people were becoming more reflective of themselves.

PF: Yeah, totally.

MR: So, I think it was definitely the right time to start a project like that and start collecting those stories. It was kind of like an anthropological curation of a time, where people were going through the same thing, and people were forced to live in these situations.

PF: Yeah

MR: Your relationships really had a mirror put up against them; there was no escape, no break. We were frozen in a moment of time, just trying to make sense of the world.

PF: Totally. It was a real magnifier and accelerator because there was no distraction. But it's interesting because this book went through many iterations to become the book it is now, because the project started in lockdown, and the stories that I received were very lockdown-specific. Another reason I wanted to do it at that time was that I genuinely didn't know how we were going to record this period in culture. Were we going to have a moment in all TV series and films where everyone stood 2 m apart, wearing masks, or are we just going to quickly gloss over it and forget it ever happened? Just erase this moment of time.

But as the project developed, I realised what other people were responding to, and what I felt had the most long-term benefits were the stories that were really universal, revealing the other side of relationships that we don't openly share on social media. So when it comes to this book, that's what I focused on: the universal story.

MR: It’s Complicated brings together over 250 new confessions. What surprised you most about the stories that came in this time around?

PF: The range of people who contributed to the project. I received stories from women in their 80s. I just thought that was so cool. I expected to have stories from people in their 20s or 30s, like dating or going through situationships, but I didn't expect to have stories from 80-year-old women talking about how they reconnected with the boy that they went to school with in 1949. I was like, oh my god, this is amazing. I also got stories from married couples telling me about the highs and lows of their sex lives or online dating in their 60’s. To see this kind of range was really interesting.

MR: You describe the book as “evidence, not advice.” Why was it important for you not to tell readers what to do?

PF: The project for me was about holding a mirror up to society and showing the reality of relationships, in a judgment-free space where people felt safe enough to share their truths. And so in order to do that, I think you have to absolutely not allow judgment and not pass judgment. One of the things I was really rigorous about was making sure people knew that in my space, we don't judge because as soon as we start judging, people will shut down, and people will start censoring themselves. This is a book saying this is who we are, I'm not saying this is who we should be, and there's something very reassuring in that.

MR: No, I love that. Some people really censor themselves and curate these perfect pages with zero conflict, but sometimes, within conflict, you find resolution. You kind of realise, wait, “we're all going through something.”

PF: Also, over the course of the project, there has been a change in the cultural and social landscape; what we share has shifted. We've gone from a time of #couplesgoal to it's embarrassing having a boyfriend, and so there has been a pendulum shift. I think we're much more open, sharing the messier stuff, like “my breakup journey”, but I do think that with anything that's a journey, there's a resolution point. So it's like taking you from a mess into an evolution. Whereas with this book, I think a lot of the time, there's no evolution; they were just moments in time. They're snapshots. And so there's nothing to compare yourself to, like " look, they healed, so I should be able to heal, too." I wanted to remove the should, I guess.

MR: Yeah

PF: I'm just going to drop you in with these snapshots and these little vignettes of relationships at different points. And I think there's something kind of different about that as well because there's no continual narrative in a way that we're used to seeing.

MR: Yeah, but I think people need that because I feel like it's like when you go to mum groups, and you share things about what you’re going through. You connect from that commonality of my god, yeah, I've been there, or I'm going through that. And I feel like that's what your book is. It's those moments you have, those conversations with people in your life, where you realise there's a common thread. You're going through the same thing, and it makes you feel, I guess, less alone.

PF: Yeah, absolutely. And I think with relationships and friendship groups, you can reach a plateau where you get less of that in a way. Like, if you're the only single one in your friends group and everyone else is married and having kids, you kind of lose that touchstone of what everyone else is going through. And I guess the book, because it has such a range, you're going to find someone that's in the same space that you are.

MR: So, going back to the whole social media aspect of it, what does this collection reveal about modern love that glossy social media narratives consistently fail to show?

PF: I think we definitely talk about dating fatigue now on social media, which we didn't say 5 years ago. But I think what the book really pulls out is the sort of damage to self-esteem that's being done because we can all be flippant and due to heteropatriarchy, but I think there's a real knock-on effect, and that's definitely sort of evidenced in the book, that people are giving up, but you might not want to give up. There's a grief in accepting that the landscape is really bleak.

There’s also a kind of erosion, I guess, on situationship shame. I feel like situationships, when you're in them, are seen as bad. And you feel like if you tell your friends they're going to tell you to "Leave him” because he's a wanker. So I think there's a double shame with that. There's like being in it and

also really knowing that everyone's going to be judging you for it. So I think the book gives space to the nuance of being in those experiences because if it were really easy and crystal clear when you're in them, you wouldn't be in them. And so what I wanted the book to give space to is to try and hold a bit more space for those experiences and show how complicated they are and how easy they are to get into them, and then how justifiable it is to stay in them.

Another thing that stood out to me is the pain of friendship breakups and being ghosted by friends. We still culturally put romantic relationships above platonic relationships. And so when we go through a friendship breakup, it's almost like we don't have the same vocabulary around that. And I think that comes up in the book.

And then a big one was ambivalence in long-term relationships and getting beyond the like “, and then we lived happily ever after” and actually being like I don't know if I want to be with this person anymore, but I'm going to continue to be with this person and showing that sort of romanticised reality online. This is really not spoken about because how can you speak about that when it's about another person, it's not just your experience now. This is a kind of shared exposure if you were to reveal that on social media. So I'm really grateful, I guess, for the privilege of being able to read all those experiences, and I hope that other people reading the book see themselves in these stories and that this book helps amplify the range of experiences we all go through, especially the ones we don't talk about.

MR: No, definitely. And I think what you were saying about friendship breakups, I feel like there is a sort of hierarchy in terms of relationship types. When I think of my friendships, I feel like there's a more sacredness to that than any relationship, because you share certain things with your friends that you may not share with your partner.

PF: And friendships really got celebrated in the book as well. A lot of the breakup stories were really about my friends pulling me through something; they're the loves, they're the support, and that's really lovely, the kind of ode to friendship.

MR: Your partner may not understand if you're in a heteronormative relationship. They might not understand your periods, pregnancy, or postpartum experiences. Do you know what I mean? You could share all the gory, heartbreaking details with your girlfriends, and they’ll understand, they’ll sympathise.

PF: Yup. They basically don't understand. Full stop.

MR: Absolutely! I do feel like there should be some sort of clear language around those sorts of breakups because it does feel the same way as ending a romantic relationship.

PF: And there's this really touching story in the book called “Ants,” which is essentially about a girl saying, “How funny that I spent so much time thinking and talking about this six-month ex-situationship that ended and never really thought about the impact until a six-year friendship ended just like that.” We expect friends to be around forever in a way, and then when they're not, that's really blindsiding.

MR: You’ve said social media has become a “device for self-torture.” What does that look like in the submissions you receive?

PF: So I think it plays out in the ex's section. It's the unavoidability of being able to see your ex or look them up online and comparing your reality and what you're going through to their presentation of what their life is like. And as much as we can cognitively say social media is not real, until we see evidence to the contrary, it could be real. They could be just one of those really happy people having a great time, and ultimately, we are still comparing ourselves to what we're seeing. So people looking on Instagram and thinking that their ex has moved on without giving them a second thought, and then feeling devastated by that and then the ex slides into their DMs 2 days later, they meet up for coffee, and it turns out they felt the same way too. It's going on social media and seeing them update their relationship status. We have so much access to seeing a version of the life your ex wants to present, and it's always the highlights, obviously. And it is just incredibly torturous and heartbreaking because you're comparing your real, lived, nuanced, deeply felt experience with a simulacrum of experience. And there's a real disconnect there.

MR: Yeah, I agree. And I think the rules of social media post breakup play a part in that, like you have to delete their photos, post a thirst trap, like “look how happy I am without you,” I'm going away on holiday, then you post an obscure picture of a random person that may or may not be my new partner. You spend so much time curating your posts to say, “I'm living my best life,” even though you're hurting. You feel like you have to put up a facade.

PF: Yeah, it's another space of performance basically, and I think we're just totally sucked into it, and as much as we don't want to, until we hear the contrary or see it, that's all we've got to go on. It's not real, but it's what we go on.

MR: No, absolutely. It's a bit of a minefield mentally as well as visually.

PF: Yeah. This is totally going off subject, but I just think social media is dying. I think Instagram is actually getting really boring, which is really helping me get off it. It's becoming just like a lecture series, and it doesn't have the same hook, which is going to be great long term.

MR: Yeah, I know. I deleted my Twitter and TikTok accounts because they were becoming way too right-wing. I only really go on Instagram and Reddit now.

PF: Yeah, totally. Yeah.

MR: Are dating apps making us worse at relationships, or simply revealing patterns that were always there?

PF: I think they're making us worse. I think what it's doing is it enables avoidance, a lack of accountability, and so it allows people to act like their worst selves, like treating people like they're disposable. There's no consequence anymore. And I think in turn what that does is it turns people into assholes. But I think even if you have no intention of behaving like that yourself, you go in with your guard up because you're so aware that people could do that, and it makes you more emotionally unavailable. Also, I feel like the whole of society is getting more and more emotionally unavailable, avoidant, hyperindependent and actually, the things we need to have good relationships are the opposite of that. We need vulnerability, safety and trust, but dating apps are essentially accelerating us in the other direction. So it has this massive knock-on effect. I mean, it doesn't look good, does it? I haven't been brave enough to do it myself yet, but I know I need to. I'm quite terrified.

Do you?

MR: I missed the whole online dating thing. I didn't get into it. I've been with my partner forever. Yeah. So the closest I got to it was the Peanut app.

PF: Yeah

MR: But, I do get what you mean about the selectiveness because you do end up picking a mum friend on the basis of their image and their likes and dislikes without actually having a conversation with them. You become so judgmental without meaning to.

PF: Yeah, it's basically enabled this disposable culture; it's making everyone super choosy and disposable. Another thing that I’ve noticed is that I don't hear women complaining that there are loads of options. Men think there are loads of options and tend to treat people as disposable, but women have a scarcity mindset because they have fewer decent options available.

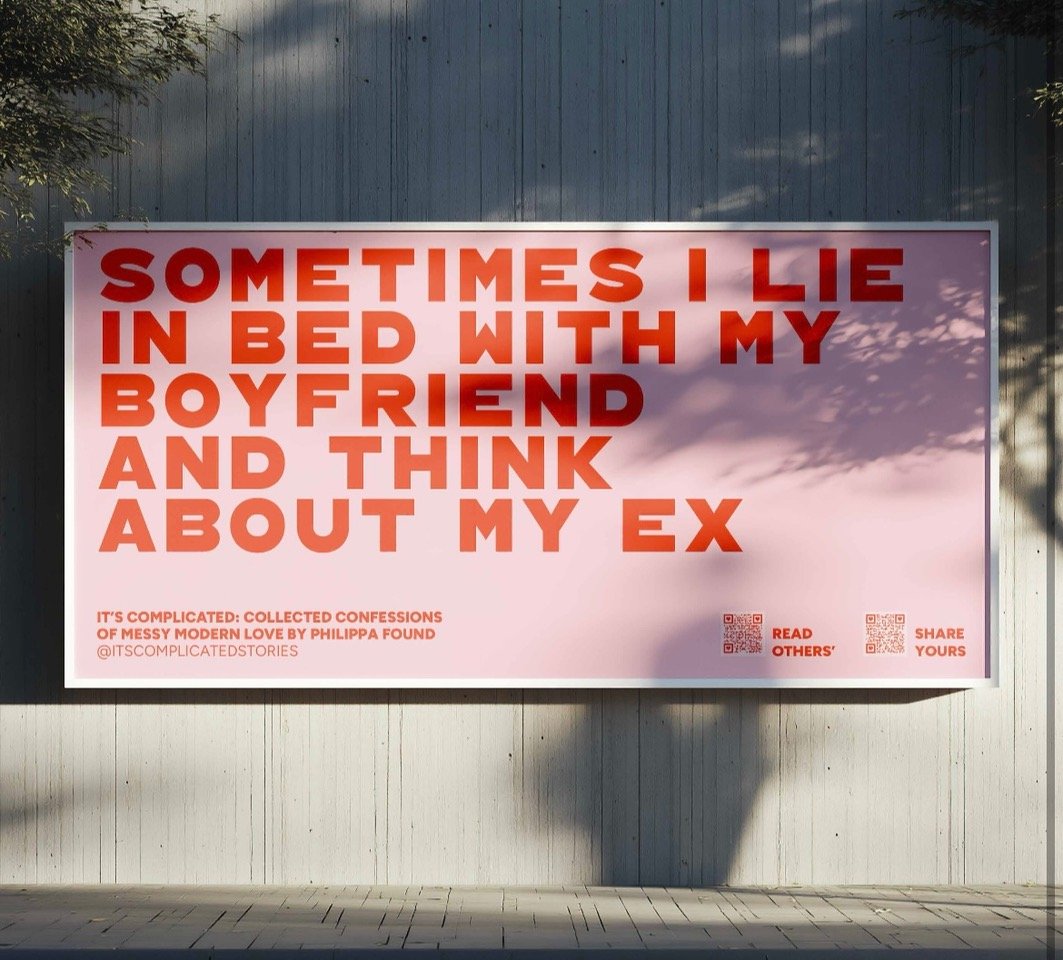

From 9–22 February, selected anonymous confessions from artist Philippa Found’s viral project will take over giant billboards across London, confronting thousands of commuters on their daily journeys as the anti-Valentine’s Day campaign goes live across the city.

MR: No, absolutely. And I think that also feeds into the whole “The loneliness epidemic.”

PF: Yeah.

MR: No, it's not us, it's you. Women don't want to be with red pill men. And instead of looking deeper into themselves and thinking, "Why am I not getting any dates or…why am I alone?" They choose to look outward and think we’re the problem. When in reality, men are the problem.

PF: I just think men haven't been socialised in the same way that women have, to enable deep, strong relationships and friendships. So many men don't have friends; they go to work, that's their role, that's their identity, and then, big surprise, “I'm lonely.” Maybe they get married, and their partner becomes their best friend, lover, their bloody cleaner, whatever.

And then the woman realises this relationship isn't really working for me, and our expectations are changing, staying in a relationship that isn't working or is no longer a badge of honour. It's like women are checking out, and then men do not have the same networks around them that women have always developed and maintained and invested in, essentially, and that's why they're lonely. I don't think they have the same literacy around their emotions, and because they're not being socialised from a really young age, and it's not their fault at all, but they're not as practised. So they're not able to make the same relationships that we are, and they're suffering from it.

MR: I absolutely agree with you. I feel like it starts with teaching emotional intelligence from a young age. You have to start teaching them about their emotions and how to communicate, and eventually, they can take that and use those lessons to form healthy, stable relationships as well as platonic relationships.

PF: It's in the books, the models that are given to men. It's all the action, and women feel so they're set off on this course of doing, instead of being taught how to feel. Yeah, it's a problem.

MR: A big one. You’ve said, “I have lived every chapter of this book.” How did reading thousands of anonymous confessions support you through your own divorce?

PF: It was monumental. Firstly, I think it was two things. It's not just me. And so the thing I was talking about, shame, as soon as I recognised myself in other people's submissions and recognised that these feelings were more common, that it wasn't just me.

I could shift from internally trying to suppress the fact that this was my experience, and I was feeling the same way. It was about allowing myself to admit it. So it was this acceptance that allowed me to make a decision and shift away from just feeling the feeling or trying to stop the feeling. And then on the flip side are the experiences that were so different to my own. When I started this project, I was married with a kid, reading stories about dating and online dating right at the start of the relationship. It was exciting, and it gave me hope, and I think the biggest heartache is almost the loss of hope. I think that's what the kind of heartbreak of breakups or long-term unhappy relationships are, and to connect with other people's hope and make you feel like maybe there could be hope in your life again; it was really inspiring in a way.

MR: What else have you learned about yourself from reading these stories?

PF: From reading these stories, what have I learned? I think I've learned that it's not just me. These experiences that feel so unique are actually really common, and it's not just me who felt this way. People would send in their submissions and be like, "You'll know it was me," and I'm like, "I had absolutely no idea it was you." We all think our experiences are so unique and so identifiable to us, but so many stories are so similar to other people's. We are living such similar narratives, and there's something really reassuring in that because we can draw strength from each other; that commonality, I think I also realised I'm a lot braver than I knew by going on this journey. I mean, I'm not the end of it, so let's see.

MR: Good luck. And I just want to say congratulations on your divorce.

PF: Thank you.

MR: I know, that's probably something you're not going to hear.

PF: Yeah, I know. Exactly. When people say, "I'm so sorry." It's like, "No, don't be sorry." Really, don't be sorry.

MR: Right! Because it was a choice.

PF: Yes, and it's a great choice to have made.

MR: Just like you made a choice to get married, you made the choice not to be. So, congratulations.

PF: Yeah, we need to celebrate these things, like put the divorce picture up and get 200 likes, not just like the wedding day picture.

MR: And you’ll definitely make it through to the other side a lot happier.

PF: Yeah. I think one of the things is authenticity and integrity, like learning through the stories, people feel happier as well when they are connected to themselves and their authentic selves. So if they're in a relationship and they don't feel like themselves, then they break up and they're back to being single. They are happier because they feel more themselves. And I think that the ultimate aim is uniting the external and internal experience within ourselves, that's when we feel our best, whether that's single or in a relationship. We need to be true to ourselves essentially and trust our feelings, and then be true.

MR: I think it's quite similar in a sense to the postnatal journey; returning to self, but then meeting your new self. It's kind of like a mirrored world of who you are now and what you want to take forward.

PF: Yeah, absolutely. There are so many parallels. One of the hardest things I found in my postpartum experience the first time around was comparing myself to other mums, like on Instagram. Seeing posts of mums looking so great and loving motherhood, being in this loving nest with their partner and the baby, breastfeeding, building businesses or writing books while their baby sleeps, and me being like, I can't even shower, how are these people doing this? I felt like such a failure, and the best thing I did was unfollow so many accounts. It's the same with relationships. We need more realness and nuance. We need to absorb a wider range of experiences so we can find the experience that identifies with our own, and then we can stop feeling so bad about our lives. Understanding and actually knowing it's not just us, and then leaning into the unique kind of qualities of our experience.

MR: I know that's why I think it's so important for mums, especially, to have really honest conversations with other mums, don't hide anything, be honest have a honest conversation about what you’re actually going through and you’ll quickly realise that you’re not alone, that you are going through the same or similar things as that mum you think has it all together.

PF: And that's why I like the stories that are the kind of darker, harder, messier. When I talk about it, it makes it sound really depressing, but for me, it's the opposite of that. It's actually so vindicating, validatingI guess. It’s reassuring because it normalises heartache, and I find it so positive reading all the negatives.

MR: No, but it's true.

PF: You know what I mean, right?

MR: Yeah. No, definitely. You feel less alone. And I think you can find positives within those negative conversations. You’ll see that your problems are not unique to you, that we’re all going through something and talking about it is like a release.

PF: Yeah. 100% agree.

MR: What is it like to hold so many unfinished stories, so many cliff-hangers, without ever knowing how they end? Do you get in touch with people and find out what happened next?

PF: Sometimes. There are people who outed themselves to me and slipped into my DMs 100%. We would go back and forth, and they would update me. I would ask questions like, “What's up? Oh my god, have you heard from him?” Or just a check in.

I am so obsessed with love stories, and there is no amount of talking that could bore me about it. I want to analyse text with you. I want to really dig deep, empathise, and highlight our similarities. I'm not going to be the person who's judging you. Do you know what I mean?

MR: Yeah.

PF: And so I would message these people and hear how they're doing. And I genuinely really care. I really am invested in their stories; they were so personal. You can't help but be moved by them. And when you're the one who's being sent these stories, even though I'm a stranger, it's such a privilege. I really connected with a lot of them. And then obviously, what was the really nice thing about the book coming out there had been a couple of years break, so hearing where they are now, years on, I saw a huge shift.

Obviously, there are some stories in the book that do play out over time. So, you do see the shifts, and I think that's so cool. There is one story called “It Was Always Meant to Be You,” which is a two-parter in the book. But you see these exes get back together and then you have an update two years later; you need to read the ex's chapter.

Seeing those stories play out showed how quickly everything can shift and turn, and that something that might seem like a happily ever after becomes not so happily ever after. I'd love to know where every single story is now.

MR: Wow! I can't wait to check it out.

PF: So it's really nice seeing those twists and turns and stuff, but how do you live with these things? You just sort of make your peace, letting these stories go and just appreciate them for the moment that they represent. Yeah, there are definitely some I'd love to be able to find out who wrote them and be like, "Did you ever get together in the end?"

MR: I don't know if I'll be able to disconnect like that. I would need to know more.

PF: I know. I definitely want to know.

MR: Six years on, what does love look like to you now, personally and culturally as we move into 2026?

PF: I think I have a better understanding of relationships. I think I also have a better understanding of myself and what I want. And I think culturally, many women have gone through that, and there's been a lot more intentional dating. Recently, I've been reading about how clear coding has been the big trend for 2026, where people are getting really clear on what they want and articulating that.

I think we've gone through this real shift from this “cool girl" thing and thinking that we understand that being “too much” was just another way of patriarchy repressing women. I'm not “too much." And actually, now getting to the point of being like, " I know I'm not too much. Now I'm going to speak up, and I'm going to be clear about what I want and believe what I want is okay.

So I think that's what love and dating look like. Whether it translates into better matches, who could say? But I think we still have a problem with an increasingly toxic landscape for dating. And it's so easy to slip into situationships and stay in them. But I think women know what they want and are not afraid to ask for it, which I think is always a good thing.

MR: I think it's this world we're in now. I think it's really good to be clear and say “I want this” because then you won't waste time, and you can get rid of people who don't want the same thing as you.

PF: The problem is when they play along with it, and then they get what they want, and then they check out six months in. Basically, what we actually need is honesty from both sides. And then when you've got honesty, you can find alignment. The biggest problem in a relationship is misalignment, essentially and then the pain that comes from that over the long term.

MR: No, absolutely. I think 2026 will be the year of honesty.

PF: Yeah. Let's hope

MR: If there’s one myth about modern relationships you hope this book dismantles, what would it be?

PF: That everyone's got a better relationship than you, whether that's with themselves, with their single life, or dating.

So stop comparing and despairing, and if you're going to compare, try comparing your life to something a little more real and nuanced.

MR: Yeah, I think that's something I didn't learn until I was probably 30. I'm only 37 now, so it wasn't that long ago.

PF: No. Exactly. I'd say I was 40.

MR: Yeah. It's just growing up, I guess. Our generation would have been the first to experience social media and all of that, so I think realising and understanding that what you see isn't real.

PF: That's why I think it's so important to have something that's so anti that, it's so raw, it's so vulnerable, it's so nuanced. It's as if our benchmark for what relationships are like was what we posted on social media; everything would be so skewed. If we can have this as a more real representational example of relationships, then we're shifting the dial because we're always going to compare, so let's at least compare our lives to something more representative.

MR: The reality instead of the facade. That's what people want, realness. People want honesty. That's what we all want right now because there is so much fakeness.

PF: Exactly. We want rawness. We want messiness. We want vulnerability because the heart is where humanness is, I guess. And I think the book goes one step further by removing the person and the face. It allows for another level of honesty, taking away the performance, which is obviously very valuable.

MR: No, absolutely. I'm really excited about it. Finally, what do you hope a reader feels when they close your book, “It’s Complicated,” especially if they’re in the middle of their own messy love story? Especially if they're in the middle of their own sort of messy love story.

PF: I want them to feel like that really helped, it's not just me. I want them to feel reassured that we are all in the messiness and all going through it, and that it’s not just them.

MR: I think it will help a lot of people. I think people will read your book and find out they're not the only ones going through something, or as you said, some of the stories are sort of almost linear throughout the book and seeing the closure at the end of a story that maybe resonates may help someone move on or make a choice.

I think this is something that we need to emphasise, that these things are normal and everyone goes through them. I think that's something lacking in our everyday lives.

PF: That's when we remove the shame, and it is that normalisation of life, re-framing those aspects as not failure but just a part of your life.

Philippa Found has become a quiet archivist of how we love, lose and muddle through connection. After capturing the raw tenderness of the pandemic era with Lockdown Love Stories, Found returns with It’s Complicated: Collected Confessions of Messy Modern Love, a braver, messier and more expansive exploration of modern relationships in all their forms. In a dating landscape shaped by burnout, blurred boundaries and emotional shorthand, her new book shifts the focus beyond romance to the sustaining power of platonic love, emotional intelligence and honest communication.